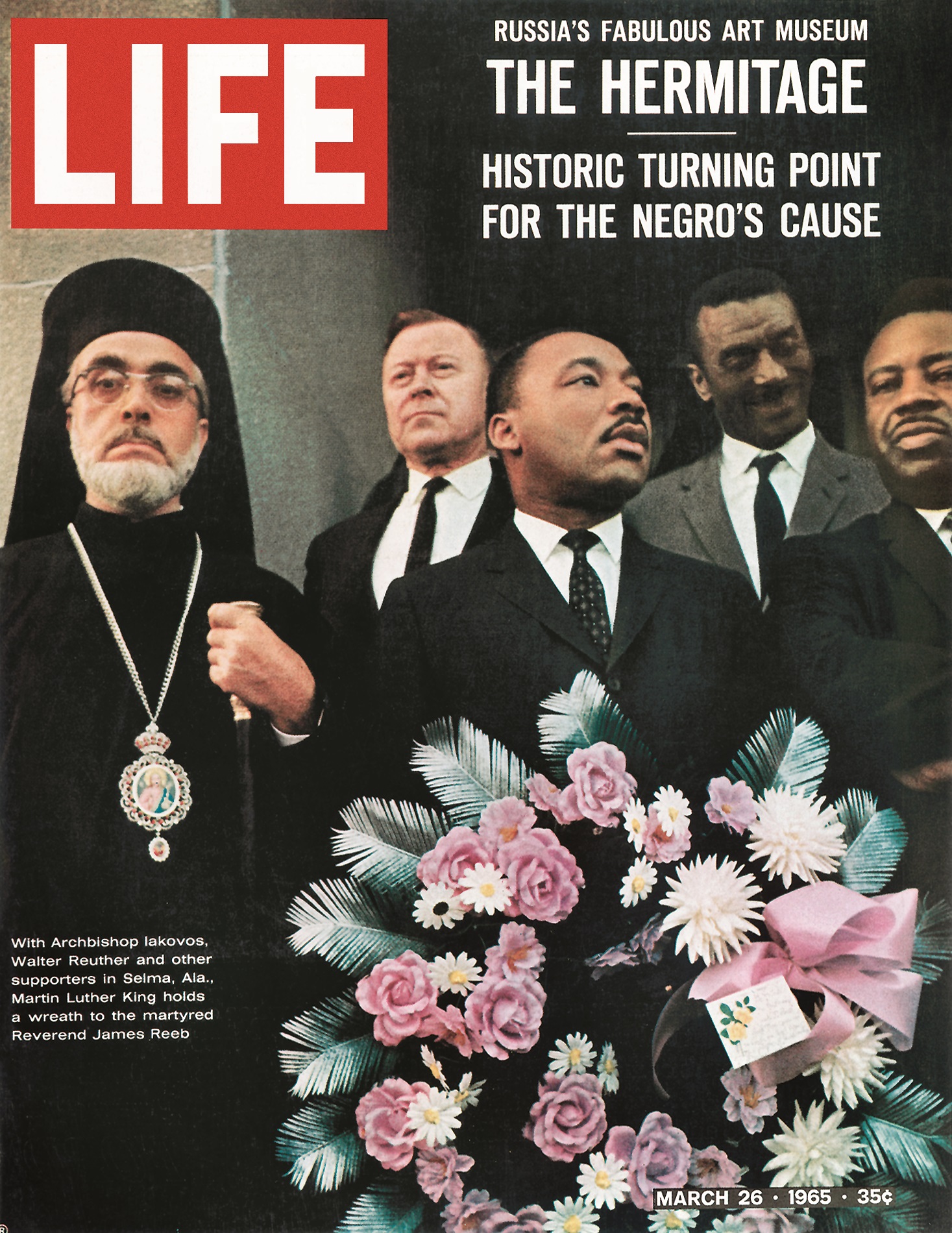

Fifty years ago, on March 15, 1965, Archbishop Iakovos, Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church of North and South America, went to Selma, Alabama and marched beside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. A moment of that day was captured on film and became the cover photograph of the March 26, 1965 issue of Life magazine. It is a compelling image. Dr. King is in the center of the photo, holding a large memorial wreath for the Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian Universalist minister and civil rights activist from Boston.

The Rev. Reeb had died four days earlier after a group of white men beat him for daring to march in a black demonstration. Although Dr. King is at the center, it is Archbishop Iakovos, solemnly gazing into the camera, that rivets our attention. The bearded Archbishop, in robes unfamiliar then to most of the American public, created a bit of a sensation in this setting. The caption, “Historic Turning Point for the Negro’s Cause,” was no doubt due to the presence of white men such as Archbishop Iakovos and Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, who was standing behind the Archbishop.

It was also a historic event for the Greek Orthodox Church in America. Archbishop Iakovos, during his 37 years (1959–96) as head of the Church in America, was photographed thousands of times with world leaders and American presidents, but it was the Life cover that became an iconic image.

Archbishop Iakovos knew discrimination first hand.

He was born Demetrios Koukouzis in 1911, during the final years of the Ottoman Empire, on Imvros, an island at the mouth of the Dardanelles. Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew was also born there in 1940. Until the middle of the 20th century, this island was the home of a large, thriving Greek Orthodox community.

The First Balkan War erupted the year after his birth, heralding a decade-long series of wars that forever altered his home and region. The young Demetrios Koukouzis experienced the first years of the fledgling Republic of Turkey as a child selling dry goods and icons in his parents’ general store, as a student at the Patriarchal Theological School of Halki where he graduated in 1934, and as a deacon of the Church from 1934 to 1939. It was a time of great political turmoil and social ferment. He understood what it meant to be a second–class citizen in the land of one’s birth. Orthodox Christians were allowed to practice their faith, but only with significant economic, social, and political restrictions. In theory, the rights of this young man and other Orthodox Christians were protected by law and international treaty. The reality of their daily life was very different.

In May 1939, when Deacon Iakovos arrived in America to become Archdeacon to Archbishop Athenagoras, he was admitted to this country as a 27-year-old ethnic Greek clergyman with Turkish citizenship. A series of laws enacted by Congress in the 1920’s had drastically reduced immigration of Greeks and other so-called “new immigrants” from southern and eastern Europe. The Greeks, Italians, and Jews were considered undesirable, less likely to learn English and assimilate into American democracy and culture. This legislation was the culmination of decades of anti-Greek sentiment in America. The Immigration Act of 1924 set a draconian quota for ethnic Greeks to 100 immigrants per year. As a clergyman, however, Deacon Iakovos qualified as a non-quota Greek. Otherwise, immigration restriction would probably have prevented or at least delayed for many years his entry into the United States.

With his personal experience of discrimination and as a Christian, it is therefore not surprising that 50 years ago Archbishop Iakovos chose to answer the call, to go to Selma and stand with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It is also not surprising that he was an outspoken supporter of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. From 1865 to 1870, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were added to the Constitution to ensure equality to all citizens, but they were not enough. Archbishop Iakovos understood from his experience in Turkey that laws offer the promise of equality and change, but an enforcement mechanism is also required.

Selma initially became a focal point in the Civil Rights Movement because of the great difficulties in registering black voters. Not long after the ratification of the 15th Amendment granting black men the right to vote, opponents chipped away at its provisions, starting with the 1876 Supreme Court decision in United States v. Reese. Many black Americans, especially those living in the South, were denied access to the polls. As a result, in 1964 only 23 percent of black adults in Alabama were registered to vote. The situation was perhaps worst in Selma, where 51 percent of the city’s residents were black, but only 2 percent (335 of 15,115 black residents) were registered to vote. This was not because of apathy. Blacks were threatened with losing their jobs and otherwise intimidated from voting. To qualify to vote they also had to pass literacy tests similar to the discriminatory literacy tests that were an obstacle to Greek immigrants after Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1917.

The fight to register Selma’s black voters had begun in 1962 but had made little progress. Dr. King knew Alabama well. His wife, Coretta Scott King, was born and raised just 35 miles from Selma. He was also a pastor in the state capital at Montgomery from 1954 to 1960. His direct involvement at Selma began on Jan. 2, 1965. The following month, less than 60 days after he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, he found himself arrested for marching without a proper parade permit and incarcerated. While in jail he quipped that there were more blacks in jail in Selma than there were registered to vote.

On Sunday, March 7, the first of three marches from Selma to Montgomery to take complaints directly to Gov. George Wallace began at the Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church. There were about 600 marchers, but they did not get far. On the outskirts of Selma at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were attacked by billy-club-wielding state troopers amid clouds of tear gas. Viewers from around the nation were horrified when they saw the graphic television footage. The second march was planned for two days later, but the 2,000 marchers went no further than the bridge. They feared being attacked by local law enforcement. This was the night that Rev. Reeb was beaten to death.

Archbishop Iakovos went to Selma for the memorial service for the Rev. Reeb and others in response to a telegram from the Rev. Dr. Robert W. Spike, executive director of the Commission on Religion and Race of the National Council of Churches, in which Archbishop Iakovos was active.

He was part of a delegation of 22 clergymen representing different denominations. Selma was dangerous, and advisors opposed his participation.

Dr. King had been assaulted there on Jan.18. Whites publicly supporting the blacks became targets, and the murder of Rev. Reeb made it clear that clergymen were no exception.

In Selma, Archbishop Iakovos attended the memorial service in Brown Chapel and then, together with almost 4,000 mourners, marched eight blocks to the county courthouse.

He left Selma that night when, in Washington, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed Congress and announced his intention to send them legislation “designed to eliminate illegal barriers to the right to vote.” This became the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965. Just as events in Birmingham are credited with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, those in Selma, which culminated in the third march to Montgomery on March 25 with 25,000 standing before the Alabama state Capitol, are said to be responsible for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It was a time of groundbreaking legislation. Later that year, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was signed into law on Oct. 3, finally ending the 40-year restrictive quota on Greek immigration.

Archbishop Iakovos’ outspoken support of Dr. King and the civil rights movement was not popular at the time.

Earlier in the century, the participation of a Greek immigrant in this kind of public demonstration would probably have resulted in deportation. Today we can look back and marvel at how much has changed in a half century and, after a cursory glance at a newspaper, lament how much remains the same. The image of Archbishop Iakovos, a man of courage and convictions, endures.

The author grew up in the American South. Twice, in 1965 and in 1970, the schools he attended were desegregated. He was a high school freshman in Memphis when Dr. King was assassinated there on April 4, 1968. See “His Eminence Archbishop Iakovos and The Civil Rights Movement: Selma, 1965” by Fr. Michael N. Varlamos at www.goarch.org for a complementary account.