This article is from PRAXIS volume 16, issue 1: "Parish as Educator."

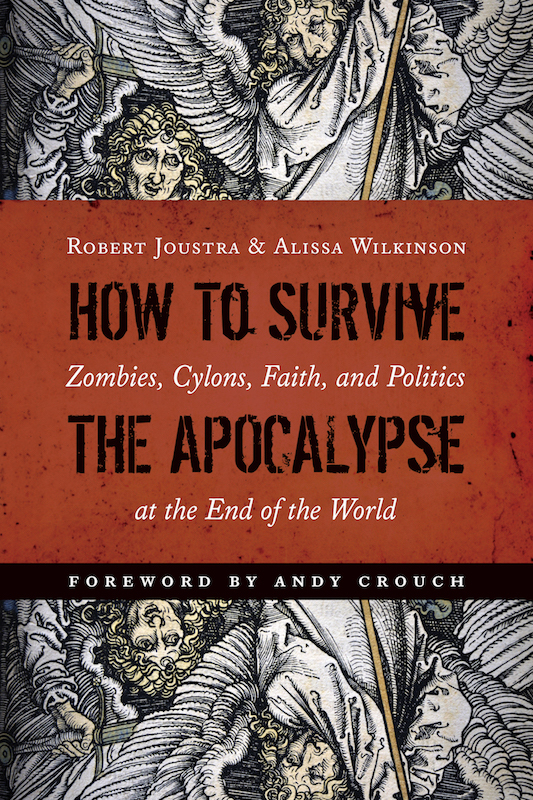

Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson tackle these stories (and more) in their book How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World. Joustra is a political philosopher and Wilkinson is a cultural critic; both are professors. Together they explore what such apocalyptic themes reveal about our present cultural mindset, anxieties and values. We find ourselves in a “malaise of modernity” (at least, according to our movies and television shows), a term borrowed from philosopher Charles Taylor’s book by the same name that provides the framework for their analysis.

You could also call it the malaise of Millennials, a demographic examined in the book and called to mind by terms like “culture of authenticity,” “hyperindividualism” and the search for one’s “true self,” all of which come into play with the identity politics that are, the authors argue, the driving force behind many of these apocalyptic narratives and the characters within them.

As the authors point out, apocalyptic stories are “not really just about the end of the world. The Greek word apokalypsis means not only destruction, not only the disruption of reality, but the dismantling of perceived realities… It renews as it destroys; with its destruction it brings an epiphany about the universe, the gods, or God” (p. 2). The end of the world—or at least, the dismantling of worldviews and societal constructs—seems to provide a prime backdrop against which to ask the question: Who am I?

The malaise of Millennials often feels self-indulgent and tiresome; indeed, watching a few episodes of Girls may be enough to convince you that the end times are upon us. But the authors insist it’s not all bad, and they show how these stories “illustrate both the pathological ways [an ethic of authenticity and the anxieties of our age] can develop and the ways they can be turned toward flourishing and good” (p. 165). Joustra and Wilkinson tap into a deeper understanding of this pursuit of authenticity, particularly the authentic self that is exalted nowadays—and it doesn’t have to be selfish or isolationist at all. The irony of the apocalyptic story is that while everything feels undone and isolated, “there is no ‘going it alone,’ because even in our struggle to be true to ourselves, we are necessarily in dialogue not only with what came before but also with people and ideas around us now” (p. 186). The apocalypse is not just an ending; it’s a revelation, and the authors’ exploration of what these stories reveal about our culture may help us as Christians respond in a hopeful and meaningful way.

Joustra and Wilkinson are smart and scholarly without being dry, and they provide enough exposition about the shows and movies discussed to make their point without spending pages and pages on plot summary. You don’t have to have seen everything they mention to follow along, although it certainly provides context and helpful mental visuals (and makes the read more fun). Needless to say, the book is full of spoilers.

Sarah Parro is managing editor of PRAXIS magazine.

Like what you’re reading? Visit the Religious Education Department to view back issues of PRAXIS and learn how to subscribe. You may also contact the Department of Religious Education by phone at (646) 519–6300 or by email at [email protected].