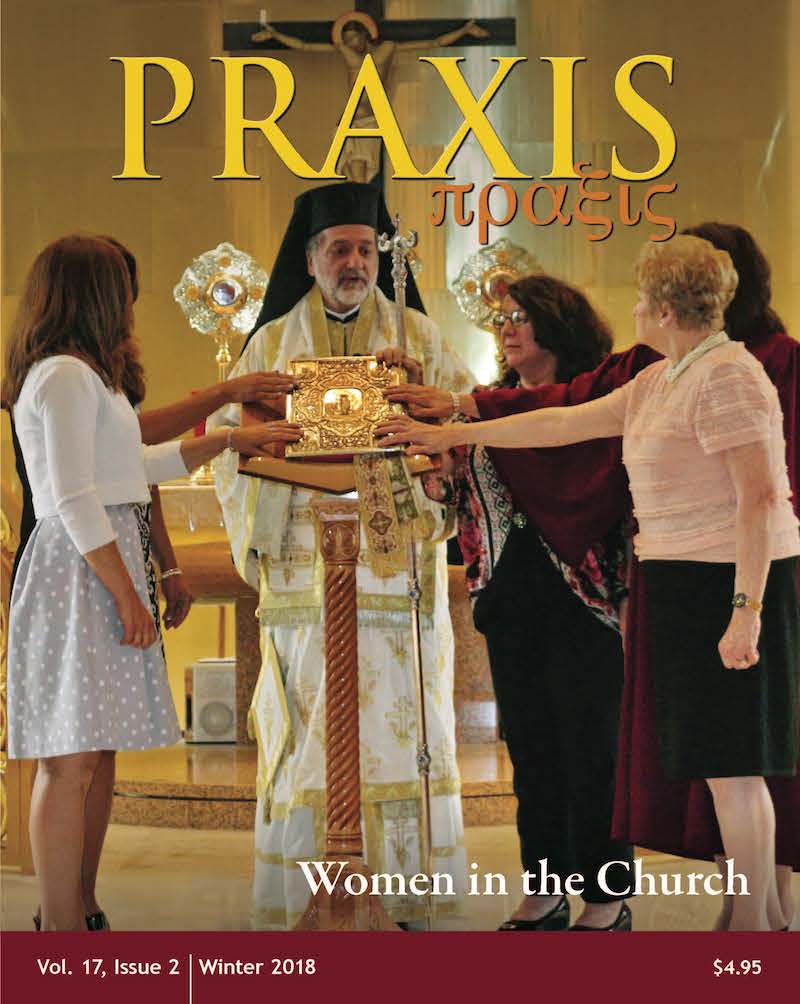

This article is from PRAXIS Volume 17, Issue 2: Women in the Church

Last year saw the publication of an article entitled “Invisible Leaders in the Orthodox Church,” which highlighted the wide variety of roles women fill within Church life. Coming to know the kinds of things that women were already doing within the Church was significant in itself, but the essay inevitably raised further questions: How and why do women rise to high levels of service in the Church? Is a seminary education necessary, useful or problematic for women who want to serve? How do women’s paid and volunteer careers intersect? To answer these questions and others, a team of researchers in partnership with Fordham University’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center launched a pan-Orthodox survey of women in the Church. Several features contributed to the significance of the process, as well as of the data that has been gathered.

We launched the survey on October 21, 2017, after a seven-month process of research and refining the questions. We identified and polled an extraordinary group of women. Participants received the survey if they had graduated from an accredited Orthodox seminary in the United States and/ or they were serving in church- or faith-related leadership or thought-leadership roles. The dizzying list of roles included: church-endorsed chaplains, pastoral counselors, spiritual directors or heads of college ministries or family ministries; church diplomats within inter-Christian and inter-Orthodox settings at the highest levels; abbesses who oversee the business and spiritual “operations” of their monasteries; women serving as founders, parish council presidents, wardens and other parish or diocesan officers, as well as trustees and directors of seminaries and other organizations; advisors sitting on diocesan, archdiocesan and even federal councils, commissions and committees on such topics as science and technology, canon law, family care, liturgy and church art, AIDS, social and moral issues and foreign policy; chief financial officers, treasurers and auditors at seminaries and at the archdiocesan, diocesan and parish levels; women holding doctorates and professorships at universities and Orthodox seminaries as theologians (liturgical, dogmatics and patristic scholars), church historians, art historians, biblical and liturgical language scholars, religious education specialists and churchspecific management and leadership professors; ecclesiastical artists and craftswomen, among them iconographers, graphic designers and illustrators, ecclesiastical tailors and textile designers producing the ecclesiastical objects that surround us and express our beliefs; and Orthodox authors, speakers, translators, bloggers, podcasters and homilists who shape and convey our thinking.

Another factor is timeliness. At a time when women’s issues overall have been rising in our political and work environments, it was instructive to examine components of women’s experience within our US churches. Indeed, many of the kinds of roles described above would be readily recognized as leadership positions in secular business or political settings. But within our churches the cumulative impact of women serving the Church rarely registers as leadership.

How and why do women rise to high levels of service in the Church?

Methodology required care and expertise: the survey was researched and created by a team of investigators of different backgrounds. In order to find out what’s working and what isn’t in their spheres, and in order to explore the various paths that women followed to bring them to their respective roles, the survey made room for stories about women’s lived experiences, unmediated by other voices. It was retrospective, meaning that the investigators were asking about events that had already happened. It ran a little over three weeks, from October 21 to November 15, and was at first distributed to 247 female Church leaders, women’s organization heads and seminary graduates and asked how they use their education (Orthodox or secular) to lead, serve and support the Faith. Over time, the number grew to 401 because of suggestions from participants. The result was a diverse and pan-Orthodox sampling, with respondents coming from a wide variety of US jurisdictions: Antiochian, Armenian, Bulgarian, Carpatho-Russian, Coptic, Greek, Orthodox Church in America, Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Serbian and Ukrainian. It also includes a small percentage of members of overseas jurisdictions who had studied at accredited US seminaries.

196 women responded, an unusually high return of 48.8 percent. Of those who responded, 51.5 percent have master’s degrees; 21.9 percent have doctorates or professional degrees (more than a few earned more than one doctorate or master’s degree). Age ranges were evenly spread from thirties through seventies, with a few outliers in their twenties or over eighty. The participants hail from thirty-one states, with the highest percentages coming from New York and Massachusetts and a small percentage from abroad. Many of the survey questions focused on backstory: what women did on the way to their current lives of service. Why is this important? As the Church looks to strengthen its mission at local, diocesan and jurisdictional levels, attention needs to be paid to the stewardship of the Church’s resources. Women are an important part of those resources and they will continue to assume significant roles in the Church’s life. Why shouldn’t the Church continue to benefit from their gifts? To that end, it is worth understanding the link between the different kinds of training women undertake and the positions that they fill: the paths women followed to the leadership roles they fill in the Church.

A preliminary look at the data shows ... that women's paths to leadership in the Church are diverse and sometimes surprising.

As the responses have been coming in, a few trends are worth noting on the way to a fuller study. A preliminary look at the data shows, for example, that women’s paths to leadership in the Church are diverse and sometimes surprising. You would think, for example, that the clearest path to leadership would be through the seminaries. And in fact well over a third of our respondents had graduated from an accredited Orthodox seminary in the United States. The seminaries’ historical mission to prepare only men for the priesthood has not curtailed enthusiasm on the part of women to seek seminary degrees, especially since seminaries train laymen and laywomen for diverse ministries. But seminary is evidently not the only path to significant service in the Church. While some seminary alumnae have made significant contributions within the Church, others have found themselves stymied. Are there patterns here to discern and lessons to learn, both for women and for our seminaries? Conversely, there are women’s organizations that operate in their own spheres for the good of their churches. Take, for example, the National Philoptochos Society. It is an organization through which women—and only women—rise to Church-related leadership. With some twenty-six thousand members, it ought to be more recognized than it is for the role that it plays in supporting important Church initiatives and institutions. As such, the survey sought to learn more about how women enter and grow into leadership within these types of organizations. We will be looking at what women’s organizations can teach other Church-related non-profits. Knowing how their members put their women’s organization experience to use in their wider work could be invaluable to strengthening the Church as a whole.

Then there are all the other routes women take that have been brought to the Church’s service: training in education, law, business, science, psychology and all the other diverse fields for which the Church needs workers and leaders. We’ll be looking at whether the women surveyed made their career, training or educational choices with a view to serving the Church or whether they identified those vocations afterward. We’ll also be looking at how the Church’s decision-makers reacted to women who sought to bring their training into ecclesial ministry. The answers resulting from this study will be presented as a report in a peer-reviewed journal in the next year and used to inform seminaries and Orthodox leaders in their efforts to strengthen our beloved Church and to help us all be better coworkers in the service of the Lord.

Patricia Fann Bouteneff, a former academic and corporate chief of staff, is a strategic communications consultant. Baptized at a metochion of Simonopetra in Thessaloniki, she has been active in church communities in Greece, England, Switzerland and the United States and at present is president of the council of Holy Trinity Orthodox Church in Yonkers, New York.

Like what you’re reading? Visit the Religious Education Department to view back issues of PRAXIS and learn how to subscribe. You may also contact the Department of Religious Education by phone at (646) 519–6300 or by email at [email protected].