This article is from Praxis 2017 Volume 16 Issue 3.

When Jesus came into the region of Caesarea Philippi, He asked His disciples, saying, “Who do men say that I, the Son of Man, am?” So they said, “Some say John the Baptist, some Elijah, and others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter answered and said, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

– Matthew 16:13–16

This exchange between Jesus and His disciples illustrates the critical reality of human experience that makes theology important: what we believe about someone shapes our response to that person. Because Peter believed Jesus was the Christ, he left his nets and followed Him. At first, his belief was not powerful enough to overrule fear or insecurity, causing Peter to deny Jesus. However, nourished by his experiences with the resurrected Christ, Peter’s belief grew stronger; it empowered this simple fisherman to become a conduit for the Holy Spirit, to preach to crowds and to heal. Peter’s conviction put him at odds with his own community and local authorities wherever he travelled. It led eventually to his martyrdom. Peter’s belief about Jesus changed his world, for himself and others.

In a similar way, what the early Christian community came to believe about childhood in the light of Christ’s life changed the world for children. In ancient pagan Roman society, before the introduction of Christianity, children were not considered to be people with the same worth as adults. Indeed, after the birth of a child, the first legal responsibility of a Roman father was to decide whether the child would be accepted into the family or disposed of. Rejected children were smothered or abandoned to death by exposure, succumbing to the elements or wild animals. If they were lucky, exposed children might live long enough to be claimed by others and raised as slaves. Parents could beat, kill or sell their children without any legal repercussions. It was freely accepted that children of lower classes, especially slave children, could be used by adults for sexual gratification. In the upper classes, children rarely commanded the direct care or attention of their parents, delegated instead to wet nurses, slaves and tutors. In short, children had no rights or dignity to speak of and childhood was, most commonly, a period to be survived. (For more on the status of children in the pre-Christian Roman Empire, see When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity, by O. M. Bakke.)

Emerging in this context, Christian theology changed the way children were understood and how they were treated. Not immediately for all children in all places, of course, but slowly and surely, as the Gospel spread, it helped create what Patriarch Bartholomew refers to in his Patriarchal Proclamation of Christmas 2016 as “the identity and sacredness of childhood.” What was it that Christians believed about children that led to such radical change?

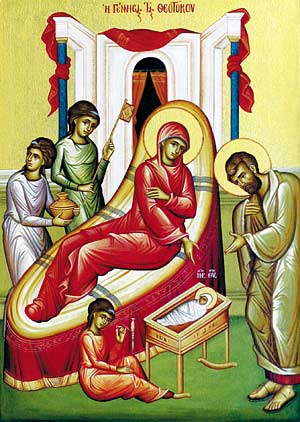

Icon by the hand of Athanasios Clark

Quite simply, Christians believed that, in Jesus, God chose to become a human being—not just an adult human being, but a fetus, an infant, a child, a youth. This meant that all stages of life and development could be united to the divine life — not just those who had come of age or who possessed a certain level of education, or those who understood moral teachings or who could practice certain rites with intention. This meant the image of God existed not only in the thirty-year-old man who could read a scroll aloud in the synagogue, but also in the partially formed embryo in the womb, the completely vulnerable newborn, the frustrating toddler, the awkward tween. How could children, born or unborn, be disposable or objects of abuse, if the spirit of God could dwell in them as fully as in an adult?

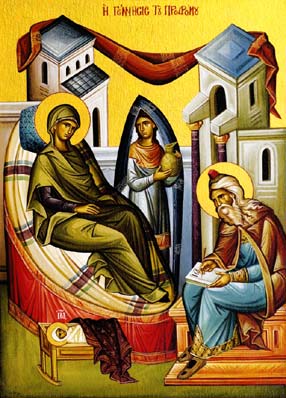

Christians began to diverge from their neighbors and believe that children were persons, inherently valuable, as valuable as adults. And, over time, that belief grew strong enough that they were willing to defy local custom. Christians became known for their teaching against abortifacients and infanticide. The Epistle to Diognetus notes about Christians: “They marry like everyone else, and have children, but they do not expose their offspring.” Christians began adopting infants exposed by others and taking in orphans, and by these means growing the Church. The liturgical life of the Church both was shaped by this belief and helped further develop it, with the celebration of the feasts of the conception and birth of Christ, the Theotokos and John the Baptist and the practices of baptizing infants and allowing them to share in the Eucharist.

Icon by the hand of Athanasios Clark

Not all aspects of childhood changed, even within the household of the Church. Christian belief in the inherent personhood and dignity of children wasn’t always strong enough to overcome certain long-entrenched practices. As was the case with slavery, the use of corporal punishment continued to be accepted and was even justified by some spiritual teachers as consonant with a Christian perspective on childhood (though others spoke against it, such as St. John Chrysostom in An Address on Vainglory and the Right Way for Parents to Bring Up Their Children). Further, as Christianity grew and diverged into various theological strands, different groups came to different conclusions about how exactly to understand and engage the spiritual realities of children—for example, whether or not children were born sinful, or whether it was really possible for a child to benefit from sacraments such as baptism and the Eucharist if they did not actively consent to them or understand them with the same maturity as adults.

In our own day, this theological and practical diversity within wider Christianity joins in a pluralistic world with countless other perspectives on children, their value and capacities, and how adults should interact with them. While, broadly, we now live in a time when the idea that children deserve protection, attention and care are commonplace, there is simultaneously still a “medley of mutually contradictory definitions of childhood” (as stated in the Patriarchal Proclamation). Consequently, a return to and reaffirmation of Orthodox Christianity’s first radical reorientation toward children is profoundly helpful; it can act as a compass needle in a very confusing reality.

In our roles as Orthodox parents, teachers and adults in our parishes and neighborhoods, we need to remain rooted in this critical conviction: God took the indignities and the insecurities of being a child seriously enough that He chose to inhabit them. The challenges and realities of childhood were worthy of His attention, His presence, His own being. And He did not engage those challenges and realities in isolation, but—even as God—He chose to subject himself to the matrix of pious parents and a wider religious community. We need to be present to children in ways our fast-paced world is not necessarily set up to support. Children need us to share our lives with them. They need us to listen to them, set healthy boundaries for them, share our experiences and struggles with them as it’s appropriate, practice virtue alongside them, support them as they try new things, receive them graciously when they fail and use our wisdom to help them develop their own. But most of all, they need us to recognize and honor the presence of Christ in them and be willing to make different and perhaps difficult choices as a result.

Matushka Jennifer Haddad Mosher (MAR, ThM) is working toward a doctorate in religion and education at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where her research focuses on the history and development of Orthodox pedagogy. She represents the Orthodox Church in America at ecumenical gatherings, teaches across a variety of Orthodox jurisdictions and lives in New England with her husband and three children

Like what you’re reading? Visit the Religious Education Department to view back issues of PRAXIS and learn how to subscribe. You may also contact the Department of Religious Education by phone at (646) 519–6300 or by email at [email protected].