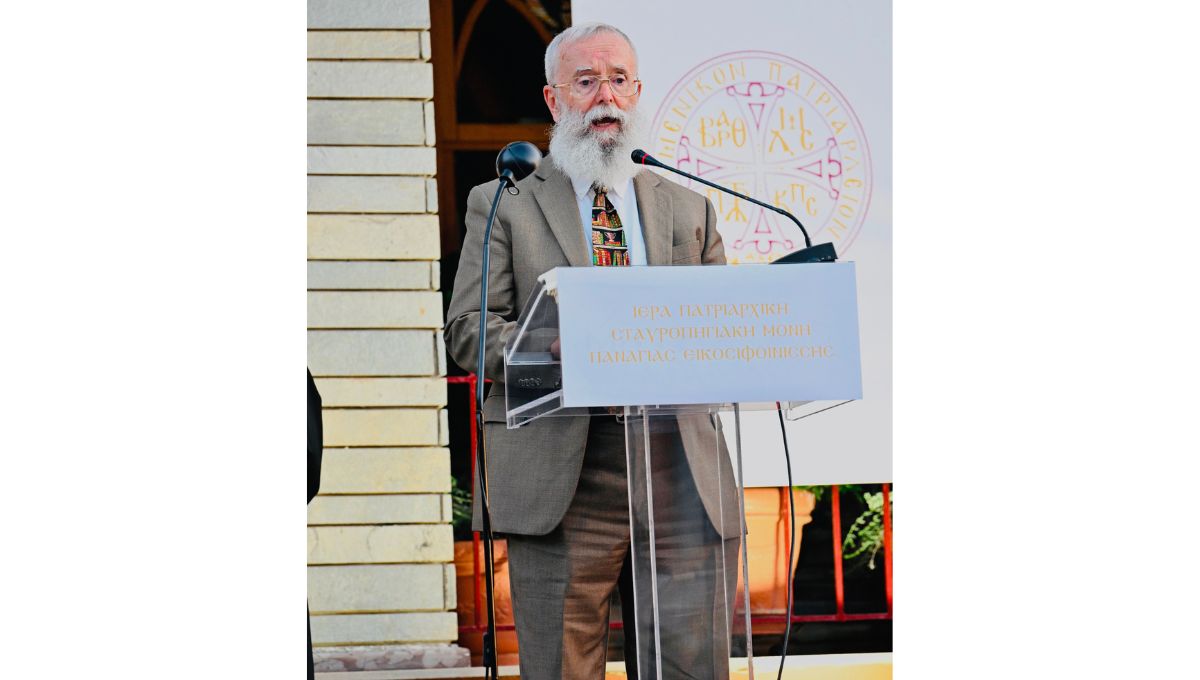

Remarks by Dr. Brian Hyland,

Associate Curator of Medieval Manuscripts at the Museum of the Bible,

At the Official Repatriation Event of Gospel Manuscript 220

Theotokos Eikosiphoinissa (Kosinitza) Patriarchal and Stavropegial Monastery

Drama, Greece

September 29, 2022

Honored guests,

For me, this story began on October 28, 2019, with a simple question at the end of an email. During the summer and fall of 2019, I had corresponded with Dr. Greg Paulson, a scholar at the University of Münster’s Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung, answering many questions about Greek manuscripts at Museum of the Bible as he and his colleagues worked to prepare a third edition of the Kurzgefaßte Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments. After answering a series of his queries, I asked him if our manuscript 352 had a Gregory Aland number, which is assigned to all known manuscripts of books from the New Testament. I attached a description of the manuscript that came from the Christie’s auction catalog. On November 6, Dr. Paulson replied with a request for images of the pericope adulterae, the story of the woman caught in adultery told in John 7:53–8:11. Fortunately, the manuscript had been fully imaged, and so I could easily comply with his request. When I found the passage in the Gospel of John, I was very surprised to see little red stars in the margin next to the beginning of each line of the passage, which started on the recto of one leaf and ended on its verso. I had never seen this before in a Greek manuscript, and so when I emailed Dr. Paulson that same day, I drew his attention to them and asked if they were something typical. In his reply, he said they were not typical at all, which is why he had asked to see the passage. He added, and I quote, “The MS is GA 1429, which has been missing for many years from Kosinitza,” endquote. He sent along a copy of the entry for GA 1429 in Caspar René Gregory’s 1909 Textkritik des Neuen Testamentes that mentioned the stars.

Kosinitza—the word practically jumped at me from the page. In earlier provenance research, I had come across the story of the terrible events that occurred here at the Theotokos Eikosiphoinissa Monastery on March 27, 1917. I also knew of the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s efforts to have the looted manuscripts repatriated to Greece and returned to the monastery. Therefore, I immediately called our Chief Curatorial Officer, Jeff Kloha, and informed him about the looted manuscript. He said that he would investigate how best to go about repatriating this manuscript and requested that I continue the provenance research on the manuscript.

This is a beautiful manuscript created by multiple scribes at a monastery in southern Italy in the late tenth or early eleventh century. The scribes wrote the text of the Gospels in a Greek minuscule script in two columns of 27 lines. One unusual feature is that the letter of Eusebius to Karpianos appears in a Greek uncial script. The decoration of the ten canon tables and the headers that appear at the beginning of each of the Gospels vary somewhat yet produce the effect of a consistent esthetic sense. The manuscript remained in southern Italy until at least the fifteenth century based on inscriptions in the manuscript. By the mid-1880s the manuscript had arrived here. Scholars in the 1880s and early 1900s described the main features of the manuscript and located it here as late as 1909. But how could I know if it was here on March 27, 1917, and was among the 431 manuscripts looted that day?

Inside the back cover, the initials M. K. appear in red pencil. To be honest, at first, I assumed they had been made by a book dealer, like the initials H. P. K. placed below it by someone at H. P. Krause booksellers of New York City in 1958. But then I had an inspiration—what if the M. K. meant Μονη Κοσινιτζα? Further research uncovered the fact that one of the perpetrators of the looting, Vladimir Sis, had made a catalog in which he indicated manuscripts from Eikosiphinissa with these initials. An online survey of manuscripts looted that day turned up images of 17 more manuscripts with the initials in the back. It was clear that this manuscript was looted in 1917.

In the course of the provenance research, I encountered eyewitness accounts of what happened here that horrible day. It broke my heart to read that the komitadji seized the two oldest monks they could find and beat them mercilessly until they revealed where the keys were. Then the partisans ruthlessly looted the monastery of everything of value. I am still horrified by what happened that day, which is why I so happy to have played a small part more than a century later in righting a seemingly unrightable wrong, and why I am deeply honored to be here on this historic occasion.

Thank you.